Asake Bomani and the Power of Telling Our Stories

Introduction

Stories are how we pass down what matters—how a neighborhood remembers its artists, how a family keeps its elders close, how a people insist on being seen. The writer and cultural organizer Asake Bomani has spent her life in this current, lifting up voices that might otherwise be lost in the noise. Her work is a reminder that telling our own stories is not a luxury. It is a form of care, a practice of freedom, and, sometimes, a quiet kind of resistance.

| Name | Asake Bomani |

|---|---|

| Born | July 1, 1945 |

| Birthplace | Wilmington, Delaware, USA |

| Education | San Francisco State University (BA in English) |

| Profession | Writer, Editor, Cultural Advocate |

| Known For | Paris Connections: African American & Caribbean Artists in Paris |

| Major Award | American Book Award, 1993 |

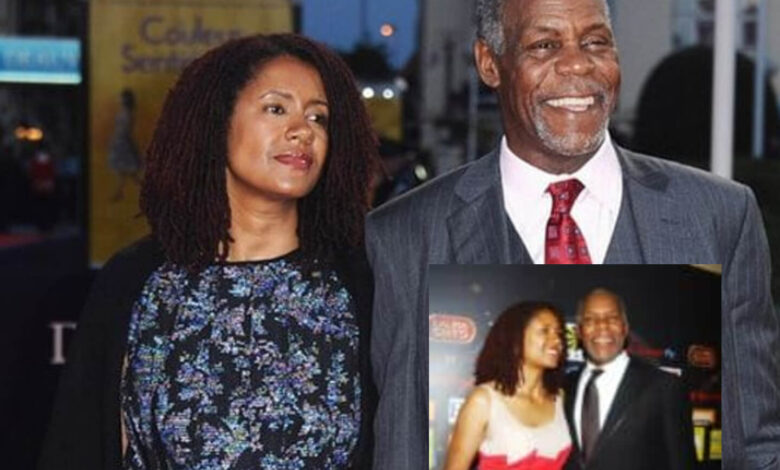

| Spouse (former) | Danny Glover (m. 1975 – div. 2000) |

| Children | Mandisa Glover (b. 1976) |

| Notable Appearance | BBC Great Railway Journeys (1999) |

| Cultural Focus | African American and Caribbean artists in Paris |

| Residence | United States (primarily San Francisco) |

| Public Presence | Private, low-profile |

| Legacy | Advocate for storytelling and cultural preservation |

A life grounded in culture

For many people, the first time they hear Bomani’s name is in connection with actor and activist Danny Glover. It’s true that the two were married for twenty-five years, from 1975 to 2000, and they share one daughter, Mandisa. But focusing only on that relationship misses the depth of Bomani’s own path. She built a record as an editor, organizer, and advocate for Black arts—especially the communities of African American and Caribbean artists who found creative oxygen in Paris.

The book that opened a window

If you want to understand Bomani’s contribution, start with the 1992 exhibition catalog Paris Connections: African American Artists in Paris (also published in a bilingual edition as Paris Connections: African & Caribbean Artists in Paris). The catalog—edited by Asake Bomani and Belvie Rooks—accompanied an exhibition in San Francisco and documented a vital creative exchange between Black artists and the city of Paris. Several library and museum records confirm the book’s details and exhibition context, including the show’s run at Bomani Gallery and Jernigan Wicker Fine Arts early in 1992.

Recognition, from peers not pageantry

The following year, the Before Columbus Foundation honored Paris Connections with an American Book Award (1993)—a prize known for recognizing literary achievement outside the usual prize circuits.

Why Paris mattered

To grasp why Bomani chose Paris as a lens, remember what the city represented to generations of Black artists and writers: the possibility to live and work with fewer constraints than were found in the United States. From the 1910s through the postwar years, figures from Josephine Baker to Richard Wright and James Baldwin made Paris a workshop of freedom. Recent scholarship and exhibitions have reinforced this history—most prominently a 2025 exhibition at the Centre Pompidou titled “Black Paris,” which mapped the presence and influence of Black artists in Paris from the late 1940s through the 1990s. The show and its coverage describe Paris as a hub for Pan-African exchange and a place where many Black American artists pursued their craft outside Jim Crow restrictions.

Telling stories across mediums

Bomani’s work doesn’t live only on the page. In 1999, she appeared in the BBC documentary series Great Railway Journeys, in an episode where Danny Glover and Bomani travel from St. Louis (Senegal) to Mali’s Dogon Country. It’s a quiet piece of television—movement, conversation, landscapes—and it fits with the way Bomani works: letting place and people speak for themselves without forcing a rigid narrative arc.

The craft: editing as care

Editors are often invisible to readers, and that invisibility can mask the labor of listening, organizing, and amplifying. Paris Connections is a strong example of editing as cultural care. The project gathered artists and writers spread across continents and languages, and presented their work in a way that centers Black creative movement rather than treating it as an aside to European modernism. The catalog records show the publication includes English and French texts and bibliographic notes, a simple detail that signals the book’s bridging intent.

A wider conversation

Seen alongside the 2025 Pompidou show and decades of scholarship about “Black Paris,” Bomani’s 1992 project looks prophetic. It anticipated renewed public interest in the transatlantic networks that helped Black artists survive and flourish—networks that were about friendship and mentorship as much as exhibitions and reviews. In this sense, Bomani wasn’t just documenting; she was helping shape the conversation about where Black art belonged and who had the authority to narrate it.

Family, privacy, and legacy

Public figures often choose how much of themselves to place in public view. Bomani has tended toward privacy, letting the work stand. What we do know is that her daughter Mandisa Glover grew up in San Francisco, forged her own path—including work in film production and later as a chef and culinary entrepreneur—and maintains a close bond with her father. That biographical thread underscores a family that treats creativity as a living practice rather than a brand.

What her work teaches

There is an ethic embedded in Bomani’s career: tell the story from within the community. Paris Connections doesn’t flatten its subjects into a generic “Black art in Paris” headline; it respects the specificity of each artist and the conditions that brought them to (and sometimes away from) the city. That approach has become more, not less, urgent as institutions correct the record on modern and contemporary art. The season of high-profile museum shows dedicated to Black diasporic modernism and Black Paris confirms the value of work like Bomani’s—groundwork that made later recognition possible.

The power of choosing your lens

Writers and editors are defined by their choices. Bomani’s choice was to focus on movement—artists leaving and arriving, carrying the sounds and textures of one place into another. Paris was the lens, but the subject was larger: how Black artists build sustenance, community, and language across borders. That’s why the catalog’s museum and library trail matters. It’s not just a book listing; it’s evidence that the stories were gathered carefully enough to be preserved.

Beyond labels

A lot of web copy reduces Bomani to “Danny Glover’s ex-wife.” The facts of the marriage are straightforward and well-documented—1975 to 2000—but the impact of that framing is worth naming. It can obscure Bomani’s editorial leadership and her role in connecting artists across geographies. Keeping those contributions at the center is part of the work of telling our stories well.

On accuracy and respect

You will find sites on the internet that claim precise details about Bomani’s birth date, height, or other personal statistics. Treat those with care. Many such claims are repeated across unsourced celebrity blogs and do not appear in reputable databases, interviews, or institutional records. A better approach—and the one taken here—is to anchor the profile to verifiable primary sources: the exhibition catalog and its library records, the American Book Award list, the television credit, and reporting on her family where it exists in established outlets. That is the minimum respect due to a writer whose career is about careful documentation.

Storytelling as a community practice

Telling your own story is not only about autobiography; it’s about who gets to be authoritative about a shared past. Bomani’s work with Paris Connections foregrounded artists who had long made Paris a site of survival and experimentation. Contemporary historians and curators continue to draw that map—tracing lines from the Harlem Hellfighters’ wartime presence and postwar bohemia to the studios and salons that welcomed generations of Black creators. When we hear that Paris served as a haven—imperfect, but freer than home—it adds texture to why a 1992 catalog about Black artists in Paris still resonates.

Lessons for writers and readers

From Bomani’s example, a few practical lessons emerge. First, do the patient work: gather names, places, dates, and let the community speak. Second, resist flattening a complex history into a single myth of exile or glamour. Third, understand that editing and organizing are creative acts—no less vital than writing a by-lined essay. Those habits help any writer or curator build work that lasts beyond a news cycle.

The through-line: dignity

If there’s a common tone across Bomani’s projects, it’s dignity. The dignity of artists who kept working even when recognition lagged. The dignity of publishing a bilingual catalog that meets readers where they are. The dignity of choosing privacy while still contributing to the public record. In an age that often rewards spectacle, that stance is its own kind of instruction.

Why her story matters now

The current swell of exhibitions and scholarship about the Black diaspora in Paris only heightens the value of early, community-rooted projects like Paris Connections. They remind us that visibility has a history, and that history has stewards. When we cite the work, seek out the catalog, or show the episode where Bomani and Glover ride the rails across West Africa, we’re acknowledging the hands that held these stories long before they became institutional priorities.

FAQs

Who is Asake Bomani?

Asake Bomani is an American writer, editor, and cultural advocate best known for co-editing Paris Connections: African American & Caribbean Artists in Paris, which earned an American Book Award in 1993.

What is Asake Bomani famous for?

She is recognized for documenting the creative lives of Black artists in Paris and for her long-standing role in amplifying African American cultural voices.

Was Asake Bomani married to Danny Glover?

Yes. She was married to actor and activist Danny Glover from 1975 until 2000, and they share one daughter, Mandisa Glover.

Did Asake Bomani appear on television?

She appeared in the BBC’s Great Railway Journeys in 1999, traveling across West Africa with Danny Glover.

Why is storytelling important to Asake Bomani’s work?

Her projects highlight the power of storytelling as a way to preserve community history, protect cultural identity, and ensure that Black artists are remembered on their own terms.

Closing

“Asake Bomani and the power of telling our stories” isn’t a slogan—it’s a description of a life’s practice. She focused on the makers and the routes they traveled. She did the editorial work that turns scattered brilliance into a record. And she insisted, by example, that our stories are strongest when told from the inside. That’s the invitation she leaves for readers and writers today: to do the work with care, to keep the past close, and to make room for the voices that are still finding their way into the light.